Culture Entry #2

Will Orman

Will Orman

The origins of Arabic calligraphy lie in the desire of

Islamic leaders to avoid using images to represent God or his creations, as

this practice might have led to idolatry. Calligraphy is also considered to be

inherently imbued with religious significance because the Qur’an was written in

Arabic. For these reasons calligraphy is used in almost all forms of Islamic religious

expression to this day.

There are various types of scripts with particular

characteristics that distinguish them. Kufic writing, which is more commonly

found in mosques in the western Arab world and also on ancient coins, can be

identified by a somewhat geometric style and a focus on horizontal lines. It is

now primarily used for decoration, usually with less readability.

Cursive styles, which are more legible and easier to write

than Kufic, were first developed in the 10th century in a movement

spearheaded by Ibn Muqla Shirazi, a Persian official in the Abbasid Caliphate.

There were originally six different scripts, though some of them are more

difficult to distinguish between for lack of examples in ancient texts. The

most common was Naskh, which was eventually used for the Qur’an and is the

basis of modern print.

Thuluth, which means one third, can be identified by the

sloping style of each letter, and it is named for the principle that one third

of each letter must slope.

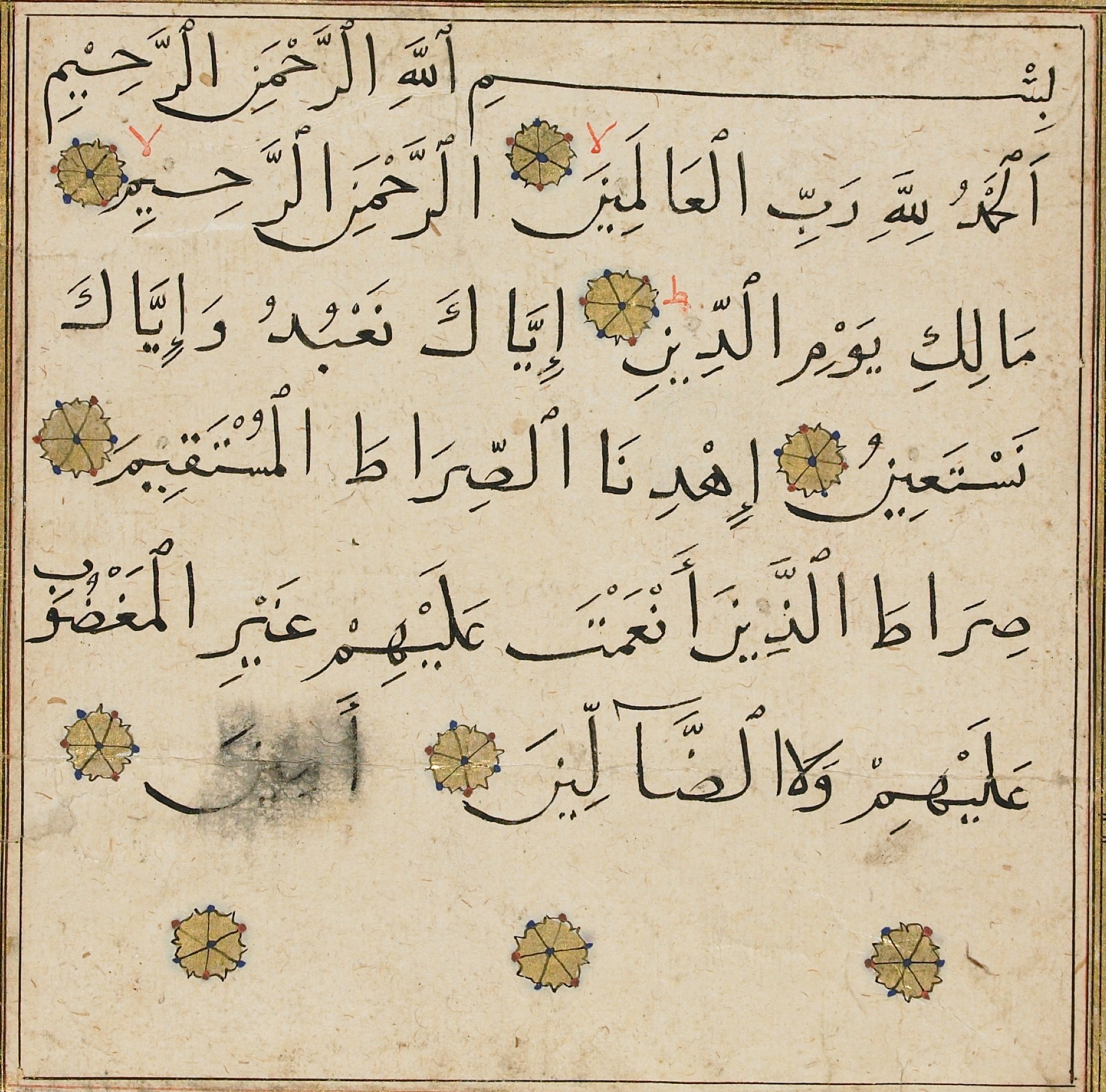

Other scripts include Tawqi’ and Muhaqqaq, each of

which have miniature versions, Riqaa’ and Rihani respectively. Tawqi was used

primarily to sign official acts, and Muhaqqaq was often used to duplicate loose

sheets of the Qur’an. The word muhaqqaq means consummate or clear, and was

originally used to describe particularly well-executed calligraphy.

Tawqi:

Muhaqqaq:

To circumvent the issue of visual representation, some

calligraphers produced calligrams, which could be human-like figures using

written words like Allah and Muhammad woven into each other, as well as animals

with religious significance and various man-made objects such as boats and

mosques. This practice is connected to Muslim mysticism and is found in many

other countries surrounding the Arab world, such as Turkey, old Persia, and

India.

Professional calligraphers generally do not acknowledge calligrams

as appropriate usage of calligraphy, but this form of expression continues to be

very popular. A graduate from my high school in Nashville, Everitte Barbee, moved

to Beirut and makes calligrams on commission, focusing on such projects as

representing the entire Qur’an with different images and occasionally on social commentary about the Arab world.

http://everitte.org/

Sources:

.jpg)